I spent a few minutes last week skimming through my unread stack of “Communications of the ACM” (CACM) – they were piling up. I enjoy the lighter articles for the most part, especially those on copyright and patent issues. The more serious articles would probably do me good to read, but no time, no time.

One bit that caught my eye: “Will MOOCs Destroy Academia?” A MOOC is a massive open online course, e.g., I’m working on one (I think there were about 15,000 sign-ups for it as of last month). I’d summarize the article as: “college courses where the professor lectures to all are ineffectual and costs are soaring [his words, not mine], but MOOCs are popular only because they’re free, and a Cambridge don says universities are critical to civilization”. His concluding sentence was particularly surprising to me: “If I had my wish, I would wave a wand and make MOOCs disappear, but I am afraid that we have let the genie [out] of the bottle.” The word “out” is in the on-line HTML and PDF versions, but not in the original print magazine. I guess the internet is good for something, though clearly not education, by the author’s estimation.

The author, by the way, is the Editor-in-Chief of CACM; I sometimes disagree with his views, but usually appreciate that some thought has been put into his opinion pieces. This time the research appears to have been the book “What Are Universities For?” and the Bible. I was cheered to see some reasonable replies.

For a CACM article with much more chew and nuance, see “Reflections on Stanford’s MOOCs“. This article is worth your time if you’re interested in a survey of various combinations of education and the internet for teaching computer science.

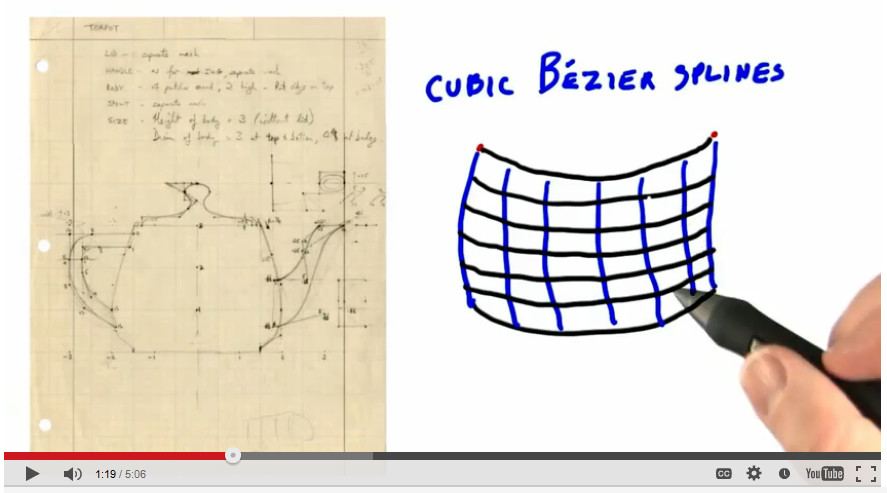

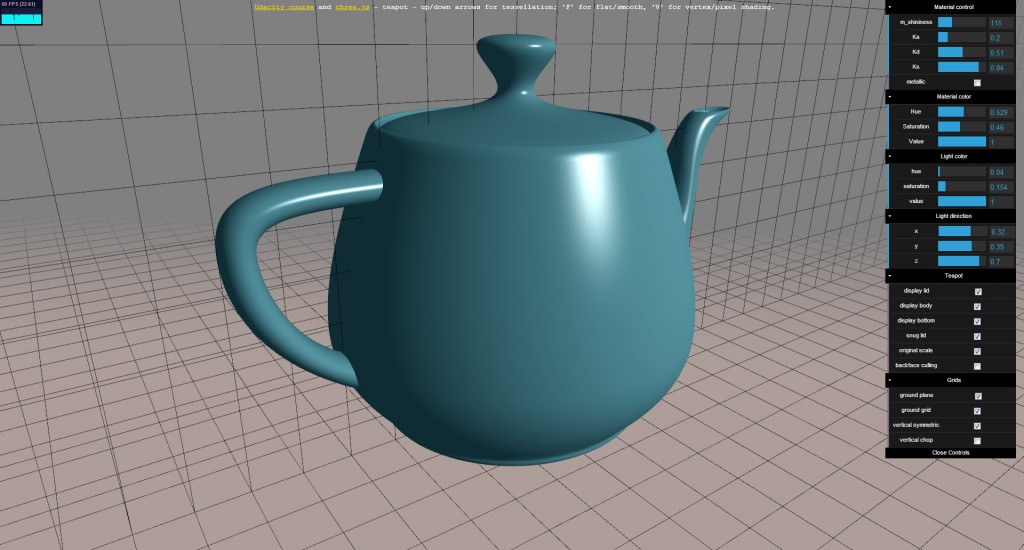

Me, I’m happy to see it’s possible to teach (in any form) using three.js on top of WebGL – click a link and you’re taken to a demo, or code you can edit and run in the browser. Try it now, if you want: for three.js demos, go to the three.js page and click on any appealing thumbnail (caveats being “use Chrome” or “enable on Safari” – see this worthwhile page if you have problems). For code in the browser, try here or any of these. For WebGL demos, some of which are wonderful, see webgl.com. And there are great things out there beyond these, I’ll cover more here once I have the time. A few days back Steve Worley pointed out this amazing thing, a classic tile terrain renderer, all in a web page.

This all couldn’t have been done at all two years ago – WebGL was officially released on March 3, 2011. This is great news for anyone teaching graphics, either online or in the classroom (or both).

Becoming a computer graphics programmer is something I consider as much an apprenticeship as a set of college courses. That’s how I felt as I began to be one at Cornell back in 1983-85. The Masters program in the Program of Computer Graphics was officially one 18 credit course each semester (and summer), along with “take a minor”. It was essentially “live and breathe graphics” for two-plus years. Teenagers in the demoscene have similar experiences, I expect.

I ran across a great quote from Confucius, which I’ll probably use at the end of the MOOC, “Every truth has four corners: as a teacher I give you one corner, and it is for you to find the other three.” This fits my view of computer graphics: you can be given a foundation in the subject, but it’s mostly up to you to learn by doing and pursuing knowledge (Confucius probably meant something entirely different). The fact that you can now do this on your own with a PC and enough self-motivation and online support I find wonderful (take the creator of three.js, for example).

Going to a college or university and learning from a good teacher and working with other students is fantastic stuff; I consider myself fortunate to have been able to do so. There are great professors and programs out there. Even humble basic courses (such as mine) are a boon, as they can expose and motivate some students to get involved and find their passion. However, the field of computer graphics (unlike, say, genetics, where you can’t currently buy a DNA sequencer for $25, but can buy a GPU for that) is quite accessible even if you can’t commit to being a full-time student.

So, back to doing my little bit to help destroy universities because, you know, that’s just the kind of guy I am. Honestly, I think MOOCs have their place, and my own vision of the future is one where professors can grab chapters, videos, githubbed code and so on to supplement their courses, and they can make their own creations available to others. They can say “take this MOOC over the summer and come back in the fall ready to go,” so that everyone has a baseline understanding.

Committing nowadays to a single textbook, for example, seems archaic. Few people have the time to write a whole book, so there are only so many to choose from and each has chapters a teacher will not use, either for time or for dislike of the author’s approach. However, plenty of people can write a short article explaining mipmaps or scaling matrices or other topics, and a few of them will be superb. Sites with educational content such as RedBlobGames, AlgoViz.org, and Online Python Tutor are signs of how things can be (BTW, I learned of those URLs from the useful CACM article). Mixing and matching among these resources allows engaging and powerful new tools for teachers and students.

Behold your doom, universities